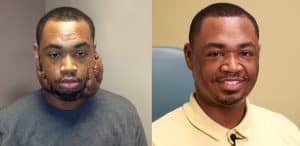

Pine Bluff Man Confident after Significant Scar Removal

| July 18, 2016 | His mother calls him the “selfie king,” and says she could not be more pleased with the fact that her son Terrance Griffin, 28, feels confident in his looks.

For many years, the Pine Bluff man was embarrassed and lived in a bubble because he had significant keloid scarring on his face. Griffin first noticed the scars when he was in the fifth grade.

“That’s when I had acne. When the blemishes healed, they formed scars. From there, we realized they were keloid scars and they kept getting worse,” Griffin said.

When skin is injured, scar tissue forms in the wound to heal it. In patients that form keloids, however, the scar tissue doesn’t stop growing and overwhelms even healthy skin, becoming larger than the original wound.

“The body doesn’t give the signal to stop healing,” said Keith Wolter, M.D., Ph.D. assistant professor in plastic surgery in the UAMS College of Medicine. “It’s basically dysregulated scarring — the body produces much more scar than it needs to.”

Wolter says keloid scars affect about 10 percent of the population and vary widely in severity. Most with keloid scars have an inherited predisposition, and the scars are more common in those with darker skin.

Griffin had felt anxious and sometimes depressed about his looks. He says strangers stared at him. He often overheard children asking their parents what happened to his face. As a teenager, Griffin began to withdraw from crowds and social interaction.

“I hated going outside the house,” Griffin said. “I would go to work and come home. That was it. I just wanted to look normal.”

Griffin had been to other doctors who removed his scars. But the problem with patients prone to keloid scaring is that the scars often grow back bigger than the original. Wolter says that’s one reason they’re so difficult to treat.

“Mr. Griffin was treated with steroid injections after his previous surgery,” Wolter said. “In some cases, that is effective. But in his case, it didn’t work. The scars led to infection and inflammation. The inflammation led to more scarring. His was the worst case I had ever personally seen.”

By the time Griffin came to UAMS, he was regularly developing abscesses within the scars on his cheeks as well as more keloid scarring. The weight of the scars was so great it was pulling his lower eyelids down, making it hard to close his eyes.

“It was very frustrating,” Griffin remembered. “I can be impatient sometimes. So when things weren’t working out like I wanted them to, I felt angry, sad and defeated.”

Griffin came to see Wolter two years ago. During a consultation, Wolter told his patient that there could be a way to remove his scars and reduce the risk that they’d come back. It included a combination of surgery, artificial skin, very thin skin grafting and radiation. It would be the first time such a procedure was done in Arkansas, and marked a novel combination of different elements that had been used elsewhere.

“I had faith in him and his medical team,” Griffin said.

Wolter performed the initial procedure in a smaller area that would not be noticeable in case it wasn’t successful. It was a staged process that included a multidisciplinary approach, working closely with interventional radiologists.

First Wolter removed the keloid scar. Then he placed artificial skin on the wound bed and treated the area with radiation to diminish the risk of the keloid scar returning. Later, they placed a very thin skin graft to the area.

“It is challenging to skin graft patients who have keloid scarring,” Wolter said. “The action of harvesting the skin graft itself can lead to new keloid scarring in the donor area”

The initial procedure was successful. Wolter had told Griffin he wanted to wait one year before going on to remove the scar on his face to make sure the keloid didn’t return. But Griffin came back much sooner, saying he did not want to wait.

“It took an incredible amount of trust on Terrance’s part,” Wolter said. “It wasn’t a trivial process for him. He had to wear a negative pressure dressing on his face for a number of days after each of the grafting treatments.”

Griffin had a total of seven surgeries to three areas where his keloid scars were most prominent: the back of his head and to the left and right side of his face. Each surgery took anywhere from one to four hours. The skin grafting process of each surgery took three to four weeks. He was completely finished with procedures after one year.

Today Griffin is two years past his surgeries and there are no signs of the scars coming back. He says his life has dramatically improved. He’s active on social media and is not hesitant to post a photo of himself to Facebook, Twitter or Instagram. His friends and family have noticed his new-found confidence.

“I go out more,” he said. “I hang out with friends and family, visit museums and amusement parks. I’m happy to be able to see the world with confidence.”