Vaccine for Existing HPV, Pre-Cancerous Lesions Shows Promise

|

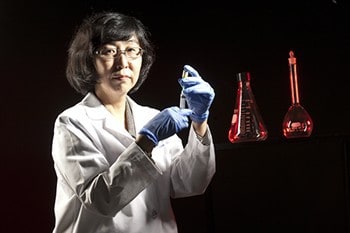

Mayumi Nakagawa, M.D., hopes to receive FDA approval for an HPV vaccine for women who are already infected and have pre-cancerous lesions.

May 9, 2014 | A potential breakthrough HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccine for women who already have HPV appears to have passed its first major test for Mayumi Nakagawa, M.D., Ph.D., at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS).

The unpublished results of an ongoing Phase I clinical trial are showing “a promising clinical response” to the vaccine and indicate that it is safe, said Nakagawa, associate professor of pathology in the UAMS College of Medicine.

HPV vaccines on the market today are used for preventing HPV only in women who have never had the virus. There is no vaccine for women already infected with HPV.

Nakagawa’s research is funded by a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). She has also received pilot funding and other support from the UAMS Translational Research Institute, which is a recipient of a NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (CTSA).

Nakagawa will present the results of the first two doses involving 12 women at the 29th International Papillomavirus Conference in August. Recruitment of research participants will continue through 2014, and the Phase I study will conclude in 2015. Preparations toward the Phase II trial are under way, and will mainly examine the vaccine’s effectiveness.

HPV, a sexually transmitted virus, is associated primarily with cervical cancer, the fourth-most common cancer in women worldwide. Cervical cancer is almost always caused by HPV, which also causes anal, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal and vulvar cancers. It is estimated to be responsible for 5.2 percent of cancer cases in the world.

Nakagawa’s vaccine could benefit women with existing infections and precancerous lesions, and new research indicates that it could significantly reduce the incidence of preterm births. It would do so by giving women an alternative to surgical treatment for HPV-related precancerous lesions such as high-grade squamous epithelial lesions (HSIL). Surgery, Nakagawa notes, was recently found to have the unintended side effect of increasing the incidence of preterm delivery, from 4.4 to 8.9 percent. Therefore, for women who still plan to have children, a therapeutic vaccine such as the one being developed by Nakagawa’s group is likely to become the first line of therapy when it is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The vaccine is the culmination of 20 years of research for Nakagawa. HPV has two cancer-causing proteins, and her group found that women who can mount immune responses to one of them called E6 had a much better outcome. Her biggest break came while studying wart treatments, when she learned that a naturally occurring yeast in the body, Candida, had an anti-HPV effect.

Nakagawa’s vaccine, which consists of synthetically made E6 and Candida, would also benefit women in developing regions of the world where surgical expertise may not be available.

“It’s very exciting because it will extend the number of women who can be helped, especially those in low resource areas where HPV disease burden is greatest,” she said.