Time to Act on Disparities, Health Equity Leader Says

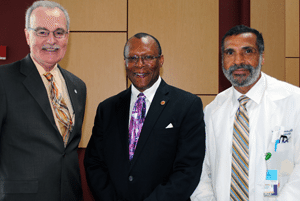

June 10, 2013 | Researchers have documented, explained and provided promising solutions for the elimination of racial and ethnic health disparities, but that hasn’t resulted in the urgency or the political will needed to advance public policy measures needed to achieve health equity, said Stephen B. Thomas, Ph.D., the founding director of the University of Maryland Center for Health Equity, during his keynote address at the UAMS Developing Health Equity Leaders Conference. “We say it is time for less talk and more action,” said Thomas, who was joined at the May 30 conference by four members of the Maryland Center for Health Equity’s leadership team. “It is time to act on what we know, and quit quibbling with P values and sample size and definitions of community and start delivering and translating our science into improving human health.” The full-day conference included a presentation by UAMS Vice Chancellor for Diversity and Inclusion Billy Thomas, M.D., Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health Dean Jim Raczynski, Ph.D., and break-out sessions co-led by UAMS faculty and the Maryland Center for Health Equity Team, including Sandra C. Quinn, Ph.D., senior associate director, James Butler III, Dr.P.H., M.Ed., Craig S. Fryer, Dr.P.H., M.P.H., and Mary A. Garza, Ph.D., M.P.H., all associate directors in the center. The conference was sponsored by the UAMS Translational Research Institute, the Center for Diversity Affairs and UAMS colleges of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Health Professions, Public Health, and graduate school. Thomas, professor of Health Services Administration in the School of Public Health at the University of Maryland, College Park, cited specific examples of health disparities, including the dramatic differences between whites and African-Americans in HIV/AIDS incidence, and research published in the New England Journal of Medicine about how physicians manage the chest pain of older black patients versus that of older white ones. The 1999 article noted that black women were significantly less likely than white men to be referred for a heart catheterization. The study concluded: “Our findings suggest that the race and sex of a patient independently influence how physicians manage chest pain.” “This is a disparity, people,” Thomas said. “We’re not going to solve this just by improving access to health care, when once you get in the health care system you experience bias and racial discrimination.” Thomas said the situation shouldn’t lead to finger pointing but rather to institutions and individual health care providers more openly addressing their inherent negative racial stereotypes. “Once you realize we all have bias, we all have prejudice, believe it or not it’s easier to deal with when it’s out in the open rather than hidden,” he said. Rather than physicians attending cultural competency classes, he said, they might prefer to gain “cultural confidence,” a phrase coined at his center that describes a lifelong process based on the provider’s self-reflection about their personal biases and prejudices. Thomas said the same issues apply to researchers who engage with those who experience racial and ethnic health disparities. “People out there are saying they’re sick and tired of being sick and tired,” he said. “They’re not seeing any improvement in their situation, and they have been studied, studied, and studied some more.” Steps taken by his center include the establishment of the Maryland Community Research Advisory Board that can help researchers more effectively engage with communities involved in their studies. The Maryland center has also mobilized black barbers and salon operators as agents for change. Called HAIR (Health Advocates In-Reach and Research), barbershops and salons have been transformed into health information portals and venues for delivery of health care services and opportunities for researchers to recruit people to public health and biomedical research, including clinical trials. In addition, the center includes the Building Trust Between Minorities and Researchers Initiative, which has developed a comprehensive training curriculum to educate the community about research and to educate researchers about respectful engagement with minority communities as the best means to conduct ethical research that is tailored to community needs. “Our goal is no less than the transformation of the biomedical research enterprise involving human subjects,” Thomas said. |